One Monday morning, before Mrs Joy Smith’s council-funded carer had arrived to help her wash and dress, debt collectors arrived at her home demanding payment of the overdue money owed to the council for her basic care.

Not a real case, nor the opening line of a new work of fiction, but typical of what goes on. This is the reality of social care in England today.

In a society where the care of our most vulnerable is already undervalued, the recent scrutiny over fines levied on tens of thousands of unpaid carers for unwittingly breaching earnings rules by just a few pounds a week highlights a deeper crisis in social care, revealing a system more focused on penalising people than supporting them.

Recent criticism from MPs on the Public Accounts Committee underscores the detrimental effects of inconsistent funding and a lack of a robust strategy to address England’s adult social care system, which supports 835,000 people.

The state of adult social care in England has reached a critical point of failure, marked by inaccessible essential care, inadequate pay and conditions for care staff, and an unsustainable reliance on unpaid carers that exposes the system’s fragility. This multifaceted crisis not only strips our society’s most vulnerable of their dignity and welfare but also places severe strains on the NHS, evident in the escalating pressures within hospitals.

Currently, social care isn’t free in England. Many, already poverty-stricken, disabled people have to pay for help with the most basics of life, including getting out of bed, going to the toilet, or having a wash. Local councils charge for this help and the charges effectively act as a tax on disability.

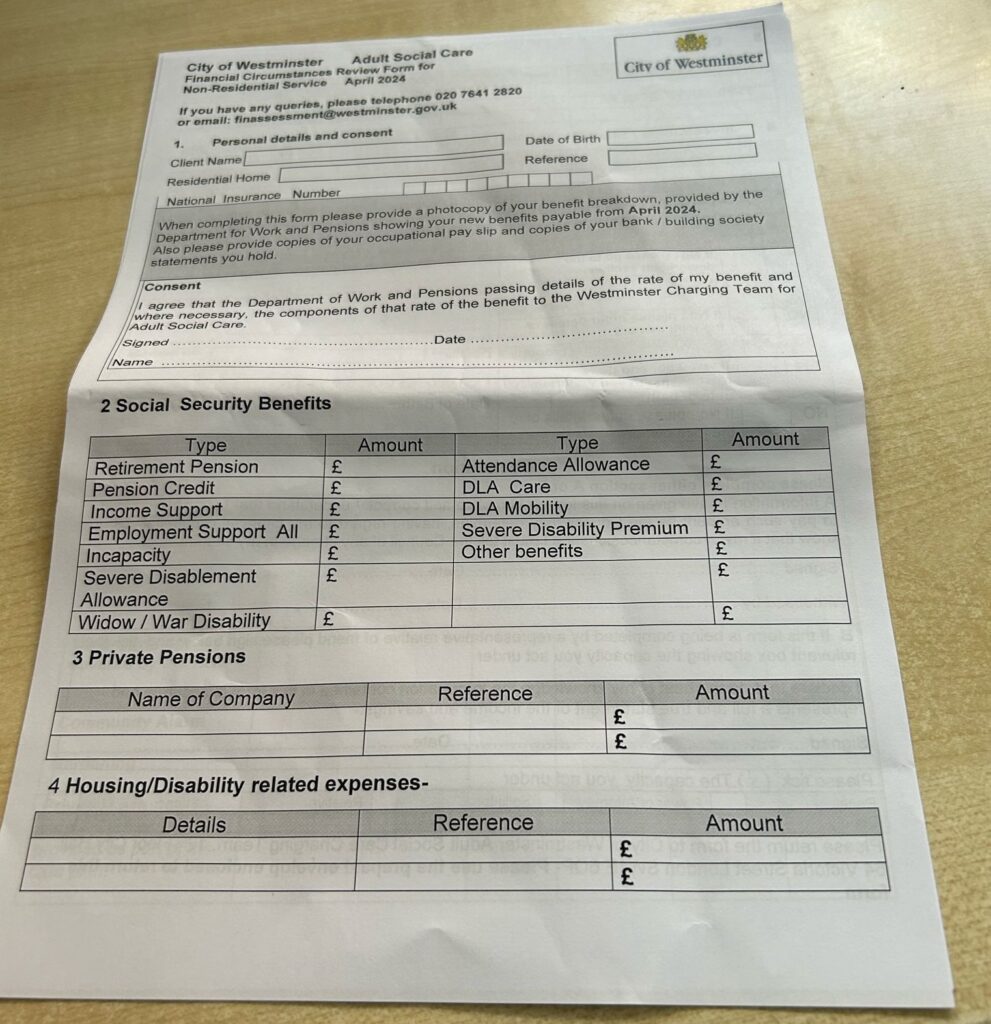

Westminster Council adult social care financial circumstances review form

This means-tested approach, which often includes a degrading and intrusive financial assessment form of several pages, not only exacerbates financial strain—some people see up to 40 percent of their limited income absorbed by charges—but also traps disabled people in a cycle of poverty, stifling their aspirations and eroding their quality of life.

The wider care landscape is tarnished by severe legal consequences for unpaid carers over minor benefits errors. They face a treacherous environment riddled with legal traps for minor administrative benefits slip-ups. A series of reports in the Guardian this past week highlighted the scandal of thousands of carers facing severe financial hardship due to penalties by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) over carer’s allowance issues the government vowed to fix five years ago.

These problems aren’t just bureaucratic blunders but indicators of profound, system failure, emphasising the pressing need for thorough reform, something successive governments have dodged for decades. This treatment of unpaid carers, without whom the whole system of care in this country would fall apart, is a disgrace.

A glaring illustration of the scandal of social care charging was Labour-run Birmingham City Council’s decision in 2022 to refer over 3,000 disabled individuals to debt collection agencies for unpaid care charges, an approach intended to recover costs that effectively penalises disability, worsening the financial and emotional strain on vulnerable members of the population.

It’s not a good time to be disabled in the UK at the moment. Disability charities last week accused Rishi Sunak of a ‘full-on assault on disabled people.’ and even the UN has picked up on how badly disabled people are being treated in this country, last month stating we are facing “grave and systemic” erosion of our rights.

As someone who personally navigates the complexities of England’s social care system and has personal experience of the means-testing of care, I face monthly council charges from my Labour-run council amounting to hundreds of pounds a month for essential support to live my life. This struggle is a reality that many disabled people live with every day, forced to allocate significant portions of our income towards accessing basic care.

Colin Hughes and Tony Blair discussing disabled people’s rights in 1996

Reflecting on a personal campaign I led in the late 1990s against the Blair government’s policy on means-testing care, it is disheartening to see after a quarter of a century, the system remains unchanged, continuing to place undue strain on those it was designed to support.

The amount of tax lost in Britain through non-payment, avoidance and fraud is around £36bn each year, according to official figures from HMRC. We should be asking ourselves why the government has failed to charge a single company under landmark legislation passed six years ago to crack down on corporate tax evasion, but feels bound to hound unpaid carers, and permits a system where local councils do the same to disabled people.

The crisis we find ourselves in demands a fundamental reevaluation of England’s social care ethos and a need for sweeping reforms that tackle the crisis’s root causes. The Conservative government has failed to fulfil Boris Johnson’s 2019 pledge to resolve the social care crisis, and now all reform is on-hold waiting the new Labour government. But will they have the courage to face up to the challenge?

Labour’s plans for reform, as announced so far, reflect a politically cautious approach – no doubt to make their policies bombproof and safe from potential Tory attacks. They lack detail, particularly on funding, and questions remain, especially regarding the party’s plan for social care charging. It is unclear if, under Starmer, promised wage hikes for carers might be financed by increased charges.

Labour MP, Paulette Hamilton, sits on the Commons Health and Social Care select committee. Until her election as MP for Birmingham Erdington in 2022, she had been Birmingham City Council’s long-serving cabinet member for adult social care – a council that sent in debt collectors to chase disabled people for social care charges.

Labour-run Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council uses external debt recovery agents. Tameside covers the constituencies of Labour’s deputy leader Angela Raynor and the party’s Shadow Minister for Social Care Andrew Gwynne.

One can only hope these senior Labour figures are against what their colleagues in local government are doing, and will work to abolish the practice if they get into government.

While Keir Starmer has criticised the government for compelling unpaid carers to repay money, he has not addressed care charges and debt recovery by Labour-run councils. This inconsistency raises questions about Labour’s commitment to addressing broader issues within the social care system.

There are a range of options for improving social care funding to provide greater protection against care costs, including Scottish-style free personal care, a cap on social care costs, and an NHS-style model of universal and comprehensive care.

Disabled people in England should be entitled to free personal care. It’s a view shared by former Labour Health Secretary and Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham, who has called for an end to the injustice of social care charging.

It’s estimated this could cost around £6 bn extra in 2026/27, rising to £7 bn by 2035/36. However, it’s important to contextualise these figures within the broader financial decisions made by the government. The decision to write off £4.3 billion stolen through fraudulent claims against pandemic support schemes, the HS2 cost overruns, and the money spent on two aircraft carriers all reveal a significant tolerance for financial loss when it benefits corporations or addresses immediate crises. This leniency contrasts starkly with the perceived hesitation to invest in long-term social reforms, which can lead to broader societal benefits such as reducing hospital admissions, promoting employment, and supporting families and carers—ultimately reflecting a compassionate and inclusive society.

Disabled people and their carers deserve better than punitive actions from cowardly political leaders constantly kicking the can of fair and meaningful social care reform down the road. The crisis in social care demands bold political courage to forge a system that is just and supportive, devoid of punitive financial burdens. Authentic social care should enable individuals to live lives marked by dignity and fulfilment, rather than subjecting them to penalties for their vulnerabilities. This shift in perspective is essential, demanding a reevaluation of how society and its governance recognise and uphold the value of care, both paid and unpaid.

With public satisfaction with social care dropping to just 13 per cent, the lowest level ever recorded, root and branch reform is something all parties should promise at the forthcoming general election.

How many more disabled people must see out their lives in a never ending poverty trap before we see change? It’s past time for decisive action. What will it take for us to realise that the cost of inaction far outweighs the price of reform?

If you are an unpaid carer facing DWP fines, or an adult social care user, contact us or share your experiences in the comments below.